Long ago before Interstate 75 was a thing, there was a very specific route ‘home’ for the thousands of Ridge-runners, Briar-hoppers, and Hillbillies living in and around Dayton, Ohio. They all had varied routes and all went “home” for every holiday, every wedding, every funeral, all graduations, moms’ and dads’ birthdays… pretty much any excuse to head south and east, back to familiar ways of talking, childhood foods, people who shared even more common experiences.

If you lived in Dayton before 1970 and your people were from the hills you followed the roads of the old Dixie Highway back home.

It just seemed old. The Dixie Hwy was cooked up in around 1914 and was one of the first projects of the National Highways Association (NHA) that was established in 1911 to launch a nationwide highway system. Their slogan, Good roads for everyone! seems so democratic, I can’t imagine not wanting to jump on board. The federal government’s first funded highway project was the National Road (now US Rt 40) in 1806, but apparently this group was getting impatient.

Dixie Highway is just what it says, a highway system for getting to the southern US. Depending on the reason for travel we’d hit the road after the parents got off work Friday night or at 5 AM on Saturday morning. We lived on Brunswick Ave. then near the Shoppers Fair, behind Giambrone’s little grocery in Harrison Township. Dad would drive us over to US Rt 25 –the Dixie Highway — via Turner Rd. That intersection was a heavily traveled road. Not a limited access like the Interstates, but people drove fast and turning out onto Dixie Drive at Timber Lane near Northridge High School was always a nerve-wracking experience.

It was nicknamed Blood-Strip because of the many, often deadly accidents and mom always, always, as we approached that area, said something about “coming up on Blood Strip” with a fear and dread of just entering the area as if it held some sinister magic that could at any second cause your car or any other vehicle to inexplicably crash. Saying “Blood Strip” out loud must have felt like control, empowering her to avoid a gruesome demise. If she was the passenger this would be noted as she gripped the dash or the door handle, pressing herself into the back of her seat. If she was the driver she white-knuckled the steering wheel and held her breath. Should be the driver Dad he was annoyed by her comments, gasping and grasping, and jitters, though I suspect no less on alert for danger.

Today there are traffic lights and the road is wider. Auto accidents are fewer and much less spectacular. Of course we now have seat belts with shoulder harnesses and safety glass, and child seats, and laws that force us to be safer; things that were not parts of our world in 1962. Back then we piled the fam into the back of the pick-up, sat the babies on our laps, and as we drove smoked our cigarettes and threw our trash out the windows, sometimes landing on cars behind. Our fathers had survived WWII and Korea. How could driving a car be dangerous by comparison?

Throwing trash out the window was about keeping a clean car; it’s right next to godliness. America was so vast and the roads to Mammaws’ and Pappaws’ were rural and seemed so isolated that our little bits of trash seemed like no big deal. Besides, many of our back-home families threw trash over the steep hillsides out of sight of the house. Burning and tossing was how trash was managed.

So, when we joked about the Baloney Rind Trail it was a reference to how we threw our garbage out our car windows as we zipped along the byways of Ohio and Kentucky, Tennessee, and Western Virginia to parts unknown by the northern natives.

Oh, and the joke was about how the working class foreigners seemed to eat a lot of processed lunch meats requiring that the casing be peeled off and discarded. mmmm, soft white bread that sticks to the teeth, Miracle whip, and bologna… but I digress.

Our northern households were second-generation immigrants of a great migration. World War II era Appalachians of every ethnicity moved north for jobs in manufacturing. The first Great Migration was of freedmen, sharecroppers, and former slaves moving north to escape Jim Crow of the early century and to find work in the cities. Coming to Cincinnati, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and settling in along the routes to the bigger manufacturing centers, African Americans came for the hope of dignity and incomes.

European Americans came from the same mountain areas for jobs as well a hoped-for bump in social status that they were sure good jobs and living in the cities would bring. Like many, my family came north to support the war effort and after, working in factories building weapons for the Allies and incidentally becoming able to afford houses and cars, chrome dinettes, cabinets filled with Tupperware, lots of shoes they didn’t wear, you know, nice things.

It created a psychic upheaval for many that we still feel even when we cannot explain the troubles. The tribes and clans were torn apart leaving cemeteries abandoned, traditions untended, and kin divided.

In 1954 Harriet Arnow published the Dollmaker (later turned into a snooze of a film as Hollywood tried to cash in on the Women’s Movement. Skip it, but definitely read the book), a fictionalized story of a family struggling with transition from a long history living in the mountains to working-class life in Detroit. While JD Vance’s story, Hillbilly Elegy, is an example of late 20th century life ‘up north’, Arnow’s story tells us more and maybe better, about why Vance’s family struggled. Her story also tells us why those trips Home were essential to the emotional survival of sons and daughters of coal miners and hardscrabble farmers.

Those trips Home for Arnow’s characters and Vance’s kin, like ours would have been on the Baloney Rind Trail, AKA The Dixie Highway.

Dixie Hwy – US Rt 25 out of Dayton to Cinci across the Ohio River and down through KY to US Rt 25W. It was an eight to none hour drive in 1962 to the Tennessee border. Today, third and fourth generations post migration, drive I75 south for 4 hours to get there.

The excitement of travel settled as we got through the scary Blood Strip moments and we headed through downtown Dayton and along the Dixie Highway out of Dayton through Middletown and the small rural crossroads. The 10 year-old me was absorbing the parental panic, but let it go by the time we get to the traffic circle.

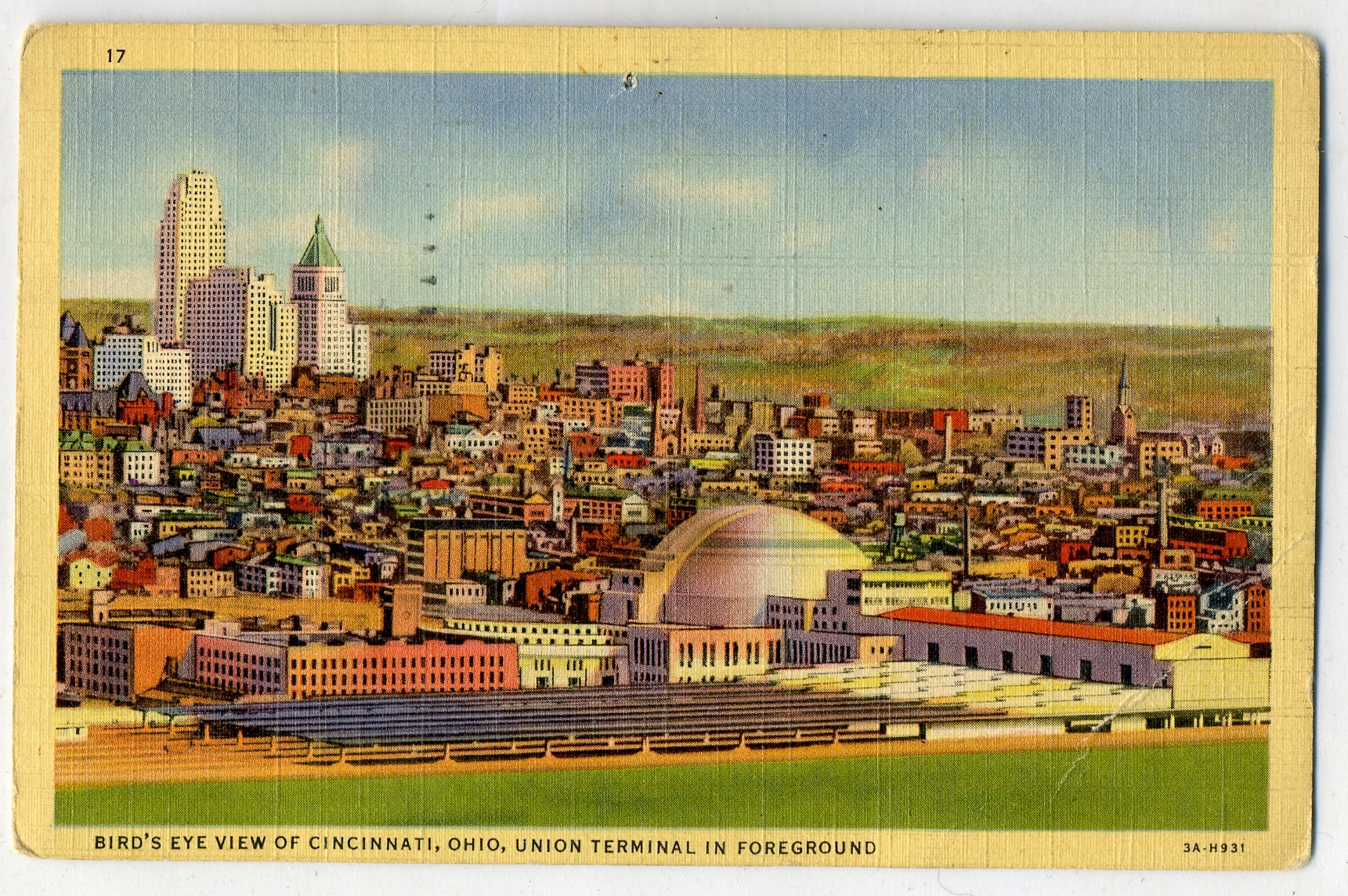

We knew we were near Cincinnati from the smell of the distilleries and closer still the smells from Proctor & Gamble stung our noses. In Dayton we appreciated the scent of baking bread passing the Wonder Bread plant on our section of Dixie Dr., but the industrial odors of the Queen City were forces to be dealt with by rolling up windows or holding our noses.

Crossing the Ohio River meant we were committed to the trip and the sights never got old. I loved watching the barges and wished I could ride them on down the river. Reading Huckleberry Finn only reinforced a dream of drifting slowly along in the big water. Later I was inspired by Harlan Hubbard’s journals of life on this river and I’m reminded that I can still dream of a life in a riverboat every time I cross from Ohio into Kentucky.

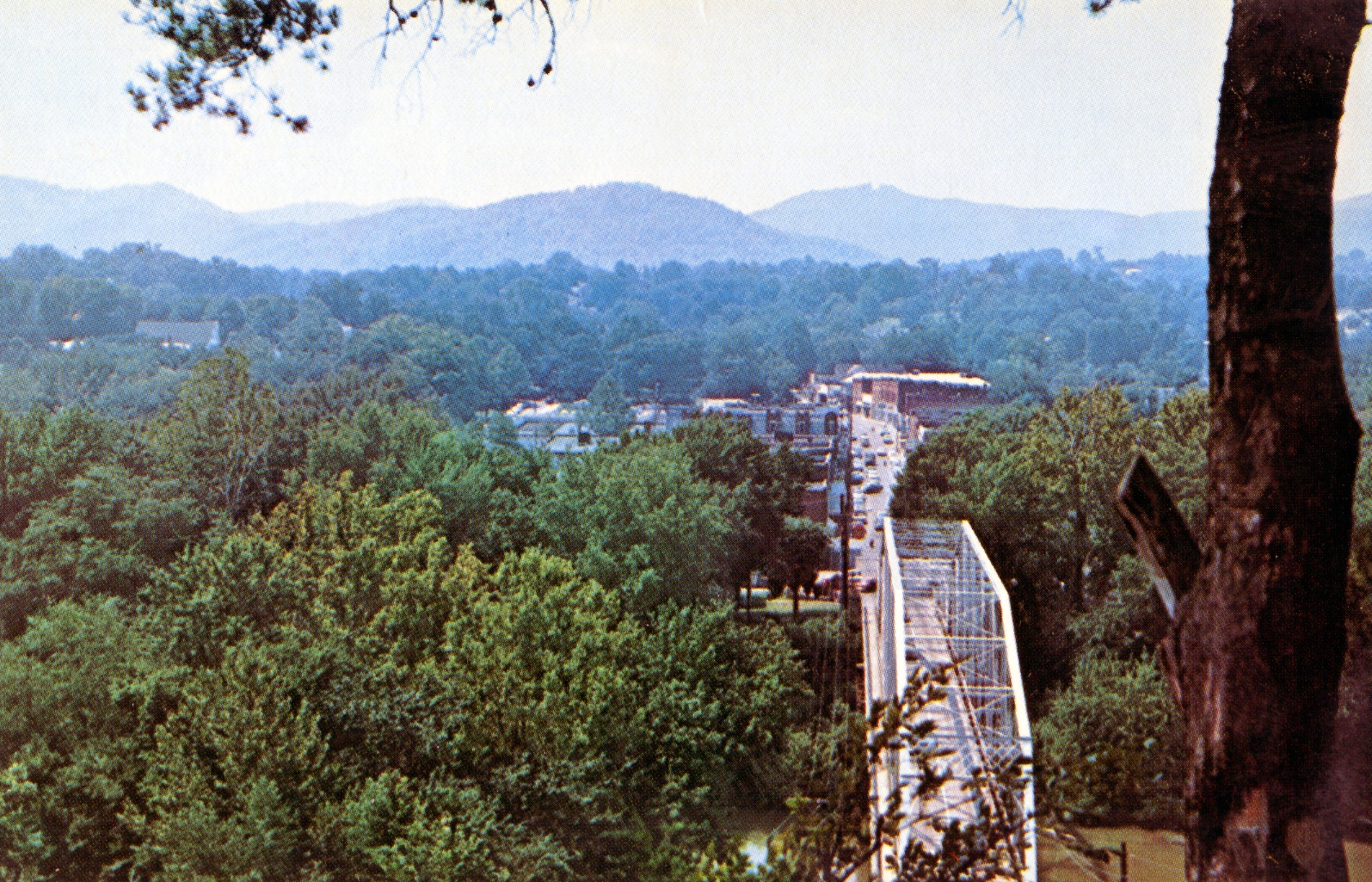

The trip took us through Covington and up the big hill where we all leaned forward as if we could help the engine drag the five of us and our too-much luggage slowly up to the level pastures of the Bluegrass on into Lexington and its white painted horse fencing. Once through the central Kentucky city the meadowlands began to rise into the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The two-lane roads no longer straight, but beginning to wind as they followed streams and inclines got steeper.

At Lexington we were four hours into the journey and made a quick stop at a roadside rest stop or a service station. Back in those days one got gas and auto service at the same place, so the oil was checked and windows washed (by a total stranger paid to do this at no extra charge to the traveler!). A white traveler could use a restroom as signs there occasionally noted, and signs along the roads would advertise ‘Clean Rest Rooms!” as a compelling reason to stop and fill-up at a particular spot. Lexington was the last convenience stop on the trip. After the lights were speeding away from the rear window it would be pit toilets and the family mayo jar, neither very desirable, no matter how necessary, for the city kids who always flushed back home.

Watching the landscape change was the stuff of daydreams as we moved out and up into the countryside. To a rock lover there were few things better than the sight of boulders and signs saying “Watch for Fallen Rock” as we wound around and through the hills. Piles of stone rubble I couldn’t find in Dayton were sirens calling me to come to them, but we never did stop; grownups couldn’t hear them singing. All I got was inappropriate stories about an Indian named Fallen Rock who had gotten lost, or irritated rejections of a large find that I wanted to haul back home when we did stop somewhere for coffee or gas.

If we reached the hills at night in the summer, we’d put our arm or head out the window and feel the air get cool and moist as we flew by rock faces with water dripping into small streams that flowed on the edges of the roads. Always the smell of earth filled our nostrils and occasionally, we could catch a whiff of honeysuckle. In winter huge icicles hung from the rocks sparkling with rainbows when the sun could strike them,but looking threatening on the shaded sides of the hills.

In the daytime, especially on weekends or through the summer tourist season, vendors would set up displays at the wide spots of country roads displaying bright colored chenille bedspreads and sometimes quilts, handmade wicker chairs, and in late summer, the sun beat down on the sellers and their bundles of native bittersweet and other produce.

Near larger towns all along the route, roadside attractions were advertised: Visit Dog Patch; See Rock City; some petting zoo whose name I no longer recall, or gift shops offering crafts. We were never allowed to stop in those days. My Dad was not the adventurous sort and he said they were just rip-offs. Once, I stopped at Dog Patch as an adult in control of my own car. Maybe an early stop at Dog Patch killed his spirit of adventure for all time. I was so disappointed.

In the days before interstate expressways there were truck stops in some of the wider spots of the Dixie Highway. It was always said you’d know the good ones by how many trucks were parked outside. That didn’t actually turn out to be the best indicator of cleanliness or even good food, however. These factors and the cost was a big part of why we packed all the food needed for the trip. Only after the coffee in the plaid Thermos ran out or got cold would there be a stop at these places, but only so Mom and Dad could recaffeinate.

The day before the trip Mom would pack bread, peanut butter, lunch meats, and Miracle Whip, sometimes cold fried chicken would be packed into Tupperware (Plastic bags had not come into being yet. Those wouldn’t get tossed out windows until the end of the decade), carrot and celery sticks would be cut up at home, maybe grapes in season, and jars of water. Lots of other food was packed into a cooler for the visit and essentials like Froot Loops, and Coca Puffs and Kahn’s Club Bologna. We didn’t always appreciate the grocery store items to found in Williamsburg, like that red-rind bologna or cans of Donald Duck orange juice.

Sandwiches were often made as we traveled along. The inedibles—paper napkins, bread crusts, meat casings, paper straws — were tossed out the windows when we were done. Trash in the early and mid sixties did not include the fast food containers of today, but there were paper bags and waxed paper from packed sandwiches and often glass bottles from beverages, and, of course cigarette packs. We hadn’t read about any Silent Spring, it wasn’t like the rivers had caught fire or anything, and Indians hadn’t yet shed a tear on our TVs. I suspect no ever got lost, because they could follow the trash trail back which ever direction they were headed.

The landmarks and my mother told us how much further we had to go and how much time we had to endure our insufferable siblings in the back seat with us. From a parent perspective the landmarks denoted how much longer they had to put up with bickering children or how many more rounds of license plate bingo had to be muddled through.

“Slow down, were coming up to Mt Vernon. It’s a speed trap, you know.” It was here each time that we passed through that a story would be retold about my mother’s younger brother outrunning a local cop by rounding a corner at high speed, turning off his headlights just before pulling into someone’s open garage.

“We’re coming to up to London. We’re almost there. Marie always likes to stop at that restaurant for fried chicken. We should do that some time.” Mom’s older sister seemed to always stop at “The Colonel’s,” as she called the restaurant, for a chicken dinner. This she would announce upon her arrival at my grandmother’s as explanation for why they weren’t there sooner. “We’d ‘av been here sooner, but we stopped to see the Colonel for some chicken.”

“We’re near Corbin. Should we take the Falls Road on into Williamsburg?” Mom’s role as tour guide was safe. “The Falls” referred to Cumberland Falls just outside of Corbin. A stunningly beautiful place with a large waterfall that features bragging rights to a moonbow, a rare thing in the world. A moonbow results when a bright full moon refracts light caught in the mist of the massive waterfall on the Cumberland River.

The glamour of Corbin, the Big City in SE Kentucky was tarnished by the signs at the city limits denoting its status as a sundown town. CBS’ 60 Minutes once did a story about the racial troubles there, an episode in its history that some deny, making the town just that much less shiny.

“Daddy always said he’d like to build a house over there. He thought that was the most beautiful spot on Earth.” It remains a lovely spot of acreage with hills on the horizon and the most spectacular sunsets. Grandpa died at the mining camp where they lived in the 1940s, never building his any home outside of a camp. His sunset views were mostly informed by hollers, hills, and how much coal dust was in the air.

The trip was nearly over after eight hours on the road when Mom pointed out that last factoid. If we “made good time” we could be at the big house on Sixth St. in Williamsburg shortly, sometimes nine hours depending on the weather. The travel time was always the second conversation after getting out of the car.

The first, no matter what time we arrived, was “Have you eaten? There’s food on the table for you.” The leftovers were almost always fried chicken, maybe a meatloaf or pork chops, but it was never bologna. Baloney was trail food.

Great story!!. I met my wife in Dayton and she was from olivehill Kentucky. While an old Louisiana boy myself I could relate to many aspects of your story. I left home at 19 spending 26 years in the military only getting home on occasion. The old adage ” You can’t got back home” rings so true.

Thanks for sharing your memories

LikeLike

Took me ” Home ” .

LikeLiked by 1 person